🧠 The Understanders research: The concerns driving AI skepticism

We interviewed 105 people to test our earlier hypotheses about AI skepticism and, well... let's just say we proved the value of testing one's hypotheses

This is the second-ever release of original primary research findings from The Understanders. Many thanks to our friends at Genway, a research platform powered by AI agents, for providing complimentary use of their tool and access to research participants to study this topic!

AI skepticism has been a recurring theme here at The Understanders lately. In the last couple of years, as AI has entered the public consciousness and discourse, much of the focus has been on the technology’s ever-improving capabilities, the flood of investment into it, and prognostications about its potential to benefit humanity and improve our day-to-day lives.

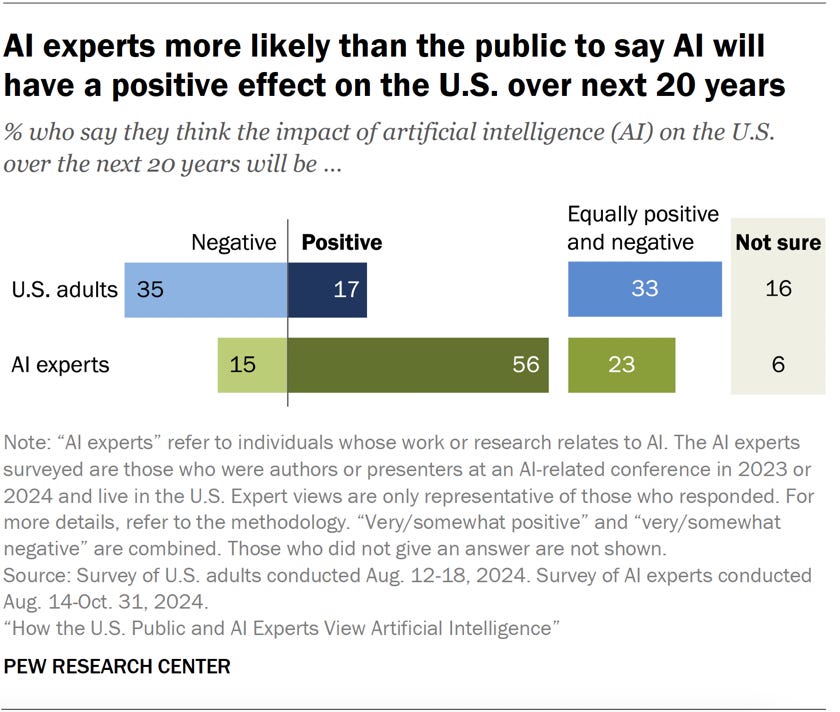

But AI skepticism— at least among the American public— is both real and measurably on the rise. The share of Americans saying AI will have a negative effect on both society and their own lives has risen meaningfully even in the last few months, according to data from YouGov. And new data from Pew shows that twice as many Americans think AI will have a negative effect versus positive on the US over the next 20 years— a balance wildly out of step with that of AI experts.

A piece in The New York Times Opinion pages, in a classic bit of how-do-you-do-fellow-kids-ism, even went so far as to declare AI a “mid” technology. Oof.

This phenomenon was real and evolving two weeks ago when we reported on the aforementioned YouGov data, but— true to the velocity of the AI space— it may have already accelerated since. Last week saw a fresh wave of negative AI sentiment bubble up online in reaction to OpenAI’s release of their 4o model’s new image generation ability and users’ subsequent use of it to mimic very specific and beloved artistic styles. It was a crystal clear manifestation of what we posited was a “moral dimension” of AI skepticism— one of several animating forces of negative sentiment that we hypothesized about when we first wrote about AI skepticism.

But that first pass on AI skepticism was just speculation, and YouGov’s public opinion data doesn’t offer much depth in terms of understanding the reasons why people feel as they do about AI. To help fill this gap in knowledge, we partnered with the research platform Genway to conduct an in-depth exploration of people’s sentiment around AI. We interviewed 105 people who have had experience using ChatGPT and led them through AI-moderated interviews designed to explore the underlying reasons for their sentiment about AI, both good and bad.

The results are a fascinating glimpse into a complex reality, where people see both promise and peril in where things are headed. But before we dive into what the interviews revealed, let’s revisit what we speculated to be some of the key dimensions of AI skepticism:

Politically-minded distrust: left-leaning people who associate AI with the newly-rightward leanings of Silicon Valley and hate it by association (this could also be called an anti-billionaire/anti-Tech/anti-VC dimension); people in this bucket don’t dismiss AI’s technological potential— in fact they acknowledge it— and some worry about job loss for humans and the rich getting richer and poor getting poorer from it

An anti- non-deterministic software dimension: folks who cite hallucinations from LLMs and bizarre media outputs (photos, videos, songs, etc.) as evidence that AI is fundamentally flawed as an approach to building useful software; these folks dismiss AI wholesale because they think it’s nothing but smoke and mirrors

A moral dimension: people who are angry that models have been trained without permission from creators, rights holders, etc. and are opposed to using them at all as a result

A fool-me-once dimension: people who think AI is simply the latest hype cycle for VCs and rich people to pump before they dump, having made their money and leaving behind a landscape of unfulfilled promises; while overlapping with politically-minded distrust, this dimension seems distinct to me, and is rooted more in a cold skepticism than a political worldview

Now here’s a scorecard for how well these either showed up or didn’t in the transcripts of these 105 interviews, as graded by Claude:

Oof. This is why we do empirical research, folks. And it’s a good reminder to be skeptical of Substack bros with hot takes.

There is indeed a dearth of evidence in the interview transcripts to support some of my ideas that AI skepticism is fueled by negative feelings around politics, the tech industry, prominent figures, or venture capital. Consider my San Francisco tech bubble thoroughly and completely popped.

Particularly off was my supposition that people’s moral concerns about AI would be mostly rooted in training data and its origins. Ethical concerns were indeed present, but tended to focus more on issues like influence, fraud or authenticity.

Zooming out, there were four big buckets of concern driving AI skepticism:

How we think and learn

Trust

Jobs and the economy

Control

The factors underlying AI skepticism were far more broadly-reaching and nuanced than I first suspected. Turns out there’s a high degree of fluency about AI’s potential benefits and drawbacks among the general population— certainly more than I assumed there was.

Here’s a look at these factors in more detail with some audio snippets from the interviews for color.

1. How we think and learn

Many participants expressed concern about AI because of how it might fundamentally change us— specifically how we think and learn. There was a fear that as AI starts to handle increasingly complex tasks, people may experience an erosion of critical thinking abilities (something we’ve seen some early indicators of), problem-solving skills, and deep understanding. The impact on education specifically came up regularly, with people expressing deep concern that students will absorb fewer and fewer cognitive skills as AI does more of the heavy lifting for them over time.

Key aspects:

Reduction in critical thinking: Many participants were concerned that AI makes problem-solving too easy, potentially eroding our ability to think deeply.

Diminished understanding: Concerns that AI-provided solutions mask the learning that comes from working through problems independently.

Loss of personal growth: Concerns about missing the developmental benefits that come from intellectual struggle.

2. Trust

Trust emerged as a common but complex theme across interviews. Participants had nuanced views on when and to what extent they trust the outputs of AI systems (primarily LLMs), and also on how the use of AI by companies and institutions impacts their level of trust in those places.

Reliability concerns were also common, of course, and extended beyond simple factual accuracy. Several participants expressed worry about AI’s ability to influence us with perceived confidence, whether it’s well-founded and -supported or not. The trust issue also connects to deeper questions about transparency— participants wanted more understanding of how AI reaches conclusions and to know who is accountable when it fails or causes harm.

Key aspects:

Accuracy problems: Concerns about AI making factual errors or producing incorrect information.

Trust in development process: Rather than distrusting AI itself, many participants emphasized distrust in how AI is being developed and deployed.

Hallucinations and fabrications: Skepticism about AI's tendency to generate plausible-sounding but fabricated information.

3. Jobs and the economy

Employment concerns manifested as both immediate personal anxieties and broader societal worries about economic restructuring. Participants often framed their job displacement fears through concrete examples of tasks they currently perform that they believe could be automated. Beyond the threat to jobs, people expressed concern about cascading economic effects from the broad adoption AI across the economy, particularly if fewer jobs lead to reduced spending.

Key aspects:

Personal job security: Concrete fears about participants' own roles being automated.

Vulnerable job tasks: Identification of particular job functions seen as most vulnerable to automation.

Broader economic concerns: Worries about societal-level economic disruption from widespread automation.

4. Control

Control concerns centered on fundamental questions about decision-making authority in AI systems. Participants expressed anxiety about gradual shifts in authority where humans might defer more and more to AI recommendations, even in domains requiring human values and judgment. There were, interestingly, multiple references across interviews to science fiction movies and pop culture as a source of this worry.

Key aspects:

Decision-making authority: Worries about humans ceding important decisions to automated systems.

Power concentration: Concerns about who controls AI systems and how that power might be used.

It’s important to remember that while this exploration focused explicitly on understanding the dimensions and contours of AI skepticism, those sentiments live alongside a lot of optimism and excitement around AI, even outside of Silicon Valley. We see these contradictions taking shape daily, it seems. Even though there was a lot of blowback to the viral Studio Ghibli trend in the wake of 4o’s newly released image capabilities, there was also a massive amount of attention, excitement, and exploration.

It’s important to not fall victim to negativity bias when trying to wrap our brains around AI skepticism. Even in these interviews, which were squarely focused on probing the root causes of AI skepticism, a lot of optimism shone through. People are genuinely excited about the technology’s implications in health care, knowledge work, productivity and education in particular.

The story is clearly more complex than just good vs. bad… and that’s what makes it so interesting.

UPDATE: many thanks to subscriber Dan for asking for clarity on the sample. It’s an important note that should’ve been included in the original writeup. The study participants were English-speaking, US-based age 18+ people who had self-reported any degree of usage of ChatGPT. The decision to filter by ChatGPT usage was made to ensure a baseline of familiarity with the subject matter.

Many thanks again to Genway, a research platform powered by AI agents, for their generous support of this study. If you’re a researcher or research-adjacent, be sure to check out their impressive product.

Super interesting as always Matt. Out of curiosity, what was the profile of the 105 people you interviewed?